Getting to Know Wild Plants

All wild plants that grow around us have a story to tell. As you pass by the hedgerow, look deep in to the nooks and crannies. This mass of green we pass by every day as we hurry to get on with our busy lives contains themedicines, foods, and tools of our ancestors. A multitude of edible plants, almost as many dye plants, even more medicines, and an abundance of plants with other practical uses reside there.

All wild plants that grow around us have a story to tell. As you pass by the hedgerow, look deep in to the nooks and crannies. This mass of green we pass by every day as we hurry to get on with our busy lives contains themedicines, foods, and tools of our ancestors. A multitude of edible plants, almost as many dye plants, even more medicines, as well as an abundance of plants with other practical uses reside there. Banished from our tidy gardens as 'weeds' these tough plants are well worth getting to know. By building a knowledge of these plants we deepen our relationship to our surroundings. Drawing us in to closely observe the subtle changes to plants such as Alexanders throughout the annual cycle, as we eat the leaves in the spring, the flowers in the summer, and then the seeds in the autumn. Notice the different microclimates on each side of a stone wall filled with pennywort and polypody hiding in the shade on one side and violets and hedge mustard growing towards to the sun on the other. Plan out your walks based on seasonal abundance, gathering foods, medicines, and materials for craft projects as you stride out.

Spring is a time for waking up. Spring is a time for new beginnings. For reaching out of our cosy burrows and meeting the world new again. On these early spring walks, we encounter fresh green edible plants such as wild garlic, three cornered leek, and hairy bittercress. These low lying plants erupt from the ground, reaching to drink in the sun before the trees above shade them out. Their strong fiery flavours wake us up from the long darkness, emboldening us to reach to the light also, firing up our metabolism and clearing our system. Watch out as wild garlic must not be mistaken with Arum Lily, a poisonous lookalike. This plant also haa single blades of green emerging from the soil. While wild garlic has soft veins all moving up the leaf, the arum lily has a very distinctive vein all the way around the edge of the leaf. Although inediblethe root of Arum Lily is a source ofstarch, historically used to starch nurses aprons.

Strong rooted plants such as nettles and comfrey crowd forth. Young nettles and some kinds of comfrey are great to eat as their deep roots have brought up rich minerals in the leaves. Their leaves are a source of pale green for natural dyeing. Chop up the leaves and soak them in hot water over night. Simmer you fabric in this water to obtain a soft silvery green.

Along the hedgerow, you will start to see cleavers and ladies bedstraw raise their tangled heads. Looking superficially similar, these plants have quite different uses. Cleavers, also known as sticky willy is a bright green climbing plant with tiny white flowers in the summer. You often find it clinging to your clothes. This is fantastic in a tea or juiced, cleaning your lymphatic system in spring. Lady's Bedstraw is a darker green non-sticky lookalike with yellow flowers. It is a humble plant with a multitude of uses. Historically, it was used to stuff the mattresses of ladies to keep the insects away. The flowers are used for a yellow dye, while the roots of this plant make a red dye. It is also traditionally used for curdling milk in the production of cheese.

Cleavers

In the spring, there are over 50 wild plants you can eat. Individually, their flavour can be overpowering, however, as you combine these plants together in to a salad or a soup, the flavours become harmonious and sing.

Originally published in Homestead Gardener Magazine

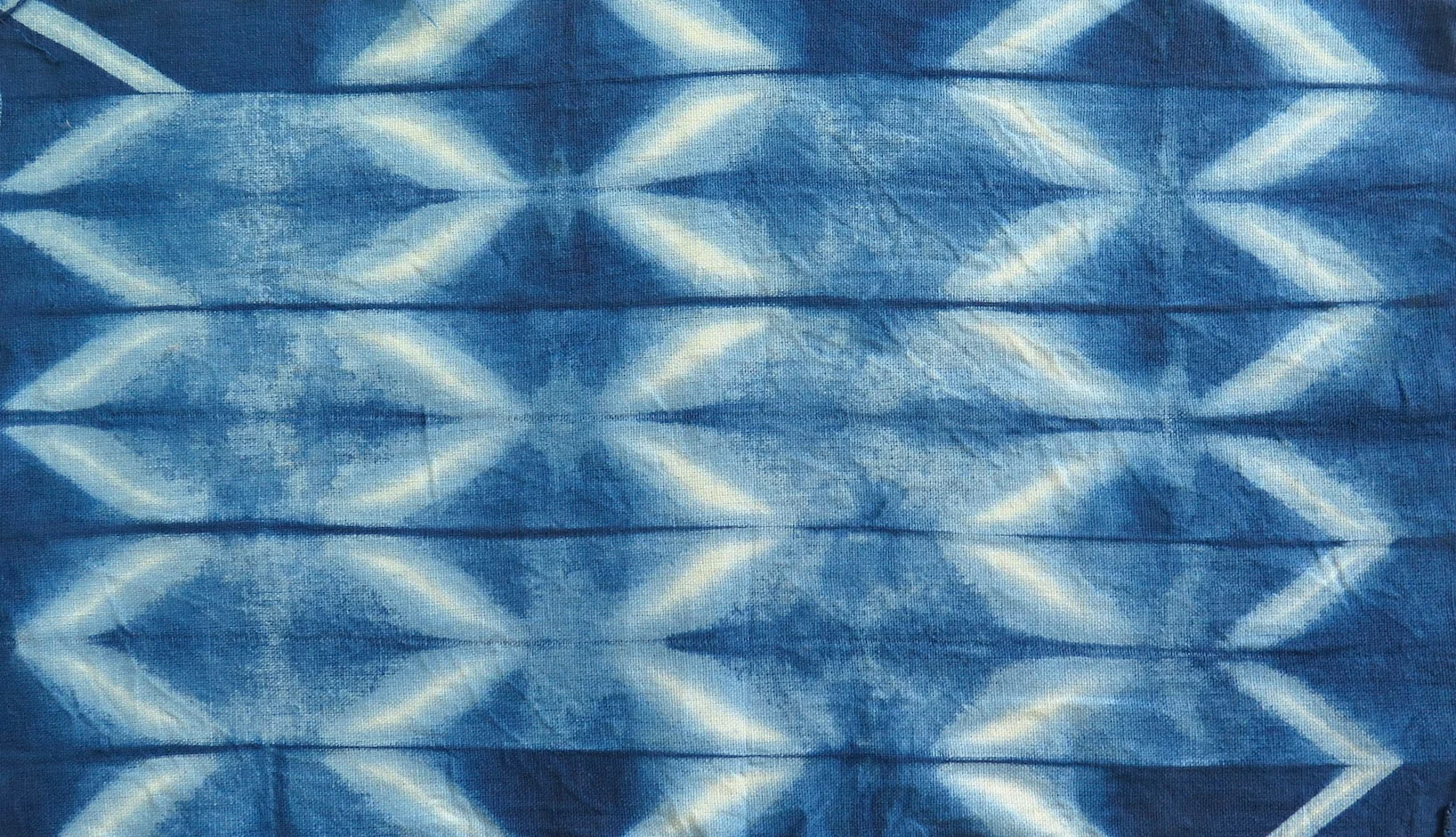

Twist, Stitch, Scrumple, Fold, Turn, Bind, or Clamp

In Japan, the shibori folded fabric is traditionally dipped in an indigo dye vat to create deep pure blue. The indigo is extracted from various plants that grow around the world, mainly Japanese indigo, Indigo Fera Tinctora, and Woad.

Whether you choose to twist, stitch, crumple, fold, turn, bind, or clamp the fabric, there are infinite possibilities of patterns with shibori.

Shibori is a traditional Japanese resist technique for creating patterns on fabric. Itajime is a quick and simple shibori technique of clamping folded fabric between two shaped blocks, fastening with a clamp, or string. The effect is satisfyingly immediate, enabling you to create dramatic geometric patterns in minutes. As well as using scrap wood to cut interesting shape blocks, it is also fun to use found objects. Buttons can be used for small circles, and jar lids are effective for large circles. Clothes pegs and bulldog clips can also make small marks with surprising effects. Bind thread around screws and baking beads for circular patterns, or simply tie the fabric in knots for a rippled effect. If you have nothing to hand, simply tying string around concertina folded fabric has beautiful effects.

In Japan, the shibori folded fabric is traditionally dipped in an indigo dye vat to create deep pure blue. The indigo is extracted from various plants that grow around the world, mainly Japanese indigo, Indigo Fera Tinctora, and Woad. The indigo is not water soluble, so a chemical or biological reaction is needed to extract the blue colour and set it in the cloth. Originally this was found through dipping fabric in a vat of indigo and stale urine (ammonia). The fabric would come out green and then oxidise in the air turning blue. Today, There are many different methods of creating an indigo vat. Michel Garcia has developed a natural method called the 1-2-3 vat combining an alkali (lime) and a reducing agent (fructose) with the indigo.

It is important to use natural fibres, such as linen, hemp, or organic cotton as the synthetic fibres will not bind with the indigo. Hand woven fabric lends itself well as the weave is looser allowing the dye to seep through the folds, achieving an even colour across the fabric, on the other hand, texture can really add to a design. Using this simple technique, of shibori and indigo, you can make yourself linen cushion covers, geometric scarves, and breathe new life in to old clothes.

Blend In To The Woods

As the nights lengthen, the temperature drops, and the energy of trees and plants goes down into the roots and outward into the seeds. This is the time for gathering the bounty of fruits, nuts, roots, and barks for natural dyeing, as well as food and medicines.

Dye your clothes with an autumn palette extracted from woodland trees and hedgerow plants, and blend in to the woods.

As the nights lengthen, the temperature drops, and the energy of trees and plants goes down into the roots and outward into the seeds. This is the time for gathering the bounty of fruits, nuts, roots, and barks for natural dyeing, as well as food and medicines.

Wild edges of hedges and woodlands are abundant with native berries. Drinking a stock of blackberries, elderberries, rowan, guelder rose, and hawthorn berries fortify our immune systems ready for the harsh winter months. Notice how they stain your skin. These berries dye fabric pink, purple, orange, and grey.

Growing in amongst the hedge is lady’s bedstraw, a straggly plant that produces a red dye from the roots. Dig up one year old dock roots and dandelion roots for golden yellow colours, and a few burdock roots to roast for your dinner. Along the riverbank, find meadowsweet roots for a black dye, this could be confused with a young bramble if not for it’s distinctive red stem, alternate tiny leaves and large leaves, and the distinctive smell of antiseptic.

Along the river, the Alder tree grows. When the tree is cut, the wood turns from white to red as if bleeding, this red dye can be extracted from the bark. In the woods, look for trees rich with tannin. The mighty oak offers a golden brown dye obtained from the tannin filled galls and small pieces of bark. This can be transformed to a black ink with the addition of iron oxide. All parts of the walnut tree are used for dyeing. The outer green cases of the nuts produce deep browns and black. Apple and cherry barks offer soft pinks and oranges. Birch bark gives tan, brown and sometimes pink.

Curiously, many natural dye plants have healing properties for the skin. Meadowsweet and oak can be used as antiseptic. Alder leaves are put in the shoes of those walking great distances to ease their weary feet. Apple is a powerful cleanser of wounds as the juice restores skin tissue. Lay the internal side of Birch bark against the skin to relieve muscle pain. Dried Lady's bedstraw is stuffed in mattresses to repel insects, and the roots are used to dye sheets to prevent bedsores. By dyeing our clothes with these trees and plants, we are healing and protecting our skin with a rich array of autumn colours that help us to blend into the season.

Originally written for LEAF! Magazine, produced by Common Ground and The Woodlands Trust in October 2016