Ruby Tayor / Native Hands

This is part of a series of blogs featuring inspiring makers who work with local natural materials.

Intimacy with the landscape, the living world, plants, earth, other creatures, has always been meaningful to me as a place of connection and belonging. So it feels completely natural to create with these materials. On an aesthetic level I feel a kinship with the textures and colours; with handling and manipulating clay and plant fibres. I think it’s in our DNA as humans to use our hands to create with these materials. I’m a gardener, growing flowers and fruit, and caretaking the places where I gather my materials. I have to work and create with my hands, it’s a kind of compulsion, an existential need. My practice means spending time outdoors in the natural world, often wandering and observing, it feels like home. I pay attention to the plants, the tress and sky; animals around me, the birds and the insects. The sensory experience of the whole process is a strong feature in my practice.

I feel strongly about not adding more stuff to the world, so working with materials and processes which are essentially low impact and degradable, pretty much a circular system, sits comfortably with my ecological concerns.

I live in Sussex at the foot of the Downs; I grew up near the Chilterns, which are also chalk; the ecosystems of both places are really similar, so I’m familiar with the plants, I’ve known them all my life. I’ve spent a lot of time in the last 10 years exploring which plants can be used for weaving, extracting fibres, creating forms.

In Sussex we’re also part of the Weald, an area rich in clay. I’ve sampled clays from many different sites and found ones that have good plasticity and integrity, and are clean enough to work with straight from the ground. I hand build, mainly using the coiling technique, in my small garden studio. I fire my pieces outdoors in the woods, either open firings or clamp kiln firings, producing low fired earthenware. The process is physical and elemental, it mirrors the very origins of ceramics- earth, wood and fire. It’s unpredictable and I like this, removing control and allowing all the variables to come into play- the weather, the firewood, the clay that came straight out of the ground only a few metres from the fire.

Plant-wise, I work with bramble, bark, rush, reeds, grass, wild rose, various leaves. I mostly forage my own materials but sometimes source from other people who harvest in larger quantities. There’s a certain insecurity inherent in relying on foraging my materials- availability varies from year to year depending on the growing conditions. I live in a densely populated county and many of my materials come from marginal places. These places are under threat from cultivation, development etc. Although I caretake as I harvest, to support the plants’ health and vigour, sometimes I’ll go to gather and find everything unexpectedly cut back by a landowner. I have a mind map of plants around where I live; it probably extends to about a 20-mile radius, but wherever I go I’m always looking around at what’s growing where, and how it’s doing.

I use a wide variety of basketry techniques, whichever works best for the plant material at hand. I don’t have a preferred method/material; I appreciate the variety and the challenge of a broad approach. The techniques have been used by humans for millennia and remain more or less unchanged. Sometimes when I’m making, I have a sense of being part of a lineage, a continuum of makers that stretches back to distant palaeolithic times; it’s mysterious and moving.

I’m interested in the dialogue between myself, my hands, and the materials. There’s often a good deal of trial and error involved in the process of making, as I get familiar with it. Sometimes I make series of pieces, often I make pieces that are one-off, responding to the particularities of the material. I’m drawn to making vessel forms. There’s a certain fullness and stillness that resonates, creates a sense of presence. The space within, a fertile void; the outer form a skin under tension: a dynamic between the two that is compelling.

In recent years I’ve made a couple of large-scale site-specific sculptural pieces, using materials foraged on site: a 7-metre-high archway in ancient woodland, and a suspended netted structure made of 70 metres of hay rope, both at Wakehurst, Kew. I relished the challenge of the open briefs of those works, responding to the place and the plants.

My current work is smaller: coiled grass vessels, various types of grass, and clay vessels. Pieces on a domestic scale, for interiors. Covid restrictions over the past year have given me more studio time; much of my work is often running courses in the woods for adults, supporting them in foraging materials to make baskets and pots. I get a lot of satisfaction from facilitating these experiences for people; I’ve also appreciated having more time recently to get into the rhythm of my own making.

My woodland courses season runs April- November, in Sussex, details on my website. I sell work through my website shop once or twice per year, and sometimes show work elsewhere. I send updates about all this via a monthly-ish newsletter https://nativehands.co.uk/subscribe-to-newsletter/

www.nativehands.co.uk @nativehands.uk

Grégoire Fournier

I am a self-taught artist, who live and work in Lyon, France. I explore the world of plant-based colors and my art include works on paper, photographs and videos, as well as songs and poems. I want to create an immersive colourful experience throughout my work and pay tribute to the plants, by showing the healing beauty and fragile vibrance of the colours they give us.

Featured Artist Series

This is part of a series of blogs featuring inspiring artists and craft people who work with local natural materials.

I am a self-taught artist, who live and work in Lyon, France. I explore the world of plant-based colors and my art include works on paper, photographs and videos, as well as songs and poems. I want to create an immersive colourful experience throughout my work and pay tribute to the plants, by showing the healing beauty and fragile vibrance of the colours they give us.

"Le passage" (crossing) - Buckthorn leaves on wooden boat on sea made of red cabbage ink - Photograph 2020

"De l'encre au pigment, de la mer à la montagne" (from ink to pigment, from sea to mountain) - Madder Lake - Photograph 2020

The whole process of making inks from plants, from picking to “cooking”, is my main source of inspiration and the object of my artworks.

The ink-making process is always unique, especially when working for the first time with a certain plant. I often see it as a ritual, as a moment when I need to be firmly rooted in what I am doing. I love the sounds, the smells, and of course all the emerging colours. Sometimes unexpected colours. When the ink is ready, I love improvising with it on papers, making stains, mixing it with other natural ingredients or other inks. I also love writing the first lines of a song or poem: about my encounter with the plant, the emotions that its colours made me feel, its name, the history and traditions it carries with it.

Sophora lake pigment and wooden masher

Althea flowers and my hand

Above all, I love experimenting and creating in a very intuitive way, see what the colours have to say, and what textures I can create with them. I like to think that I am just following the energy of the ink or plant, just as I if I was letting myself go in a river’s flow. During that journey, I enjoy making mistakes and usually see them as a great opportunity to make up new things.

Besides works on papers, I also talk about the magic of natural colours and dyeing plants through photographs and videos. With the photographs, I create a whole new scenery or landscape where the plants and colours are the main subjects. In order to so, I use dyed textiles, dried plants I cooked as part of the dying process, and some natural materials I found during my walks. I imagine rituals during which I pay tribute to the plant, and to the colours they give us as gifts. Through videos, I intend to show the magical journeys of plant-based inks on paper, and their unforgivable colourful encounters. I want people to witness what happened on the paper, before the inks dried out. I believe videos can offer an immersive experience, a way of meditating with colours and traveling freely into an imaginary world.

Why do you choose to work with natural materials?

Working with natural materials is very meaningful to me. It allows me to really connect to the place I live and to the natural world, to grow roots where I live, follow the seasons and always learn new things. Nature offers unlimited possibilities, and so many opportunities to create and make up new processes, new techniques, new ways of expression. To me, it is the greatest source of inspiration, the greatest source of materials, tools, textures. Art is everywhere in nature. Sometimes we just need to take a break, look around us and appreciate the beauty of what nature offers. I think it is the very first step of the creative process. As for natural colours, they are very vibrant, powerful, full of life, even if they are supposed to be more fragile. Colours, are just like anything else; they disappear at some point. But the memories and relationships we, as human beings, build with them, last through time.

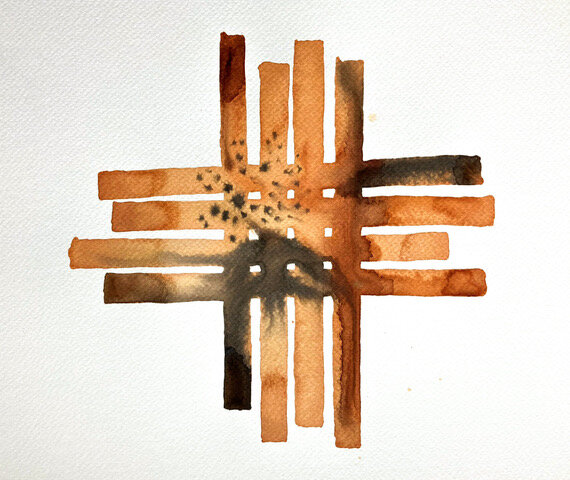

"Birth" - vegetal inks on cotton paper 40x40 cm - 2020

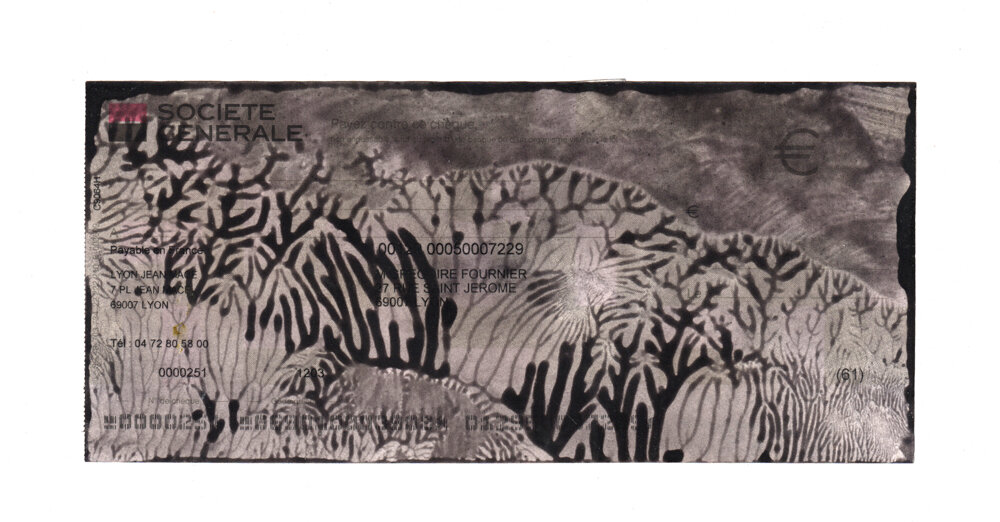

"Chèque en bois" - vegetal inks on check - 2020

Taking Over - Red cabbage ink on paper 70x50 cm - 2020

Where do you live and how does this influence your process of working with natural materials?

I live in Lyon, the second most populated city in France. Even if I am constantly dreaming of living and working in the countryside, close to nature, I think work needs to be done in cities. Using natural resources from the city (I find many things through the seasons) is also a way of showing that we need more nature in our urban environments. I think it is essential to make the inhabitants aware about the natural wealth of their city so they start taking care of it and asking for more: more trees, more parks, more flowers, more plants, more animals. Less cars, less concrete. More than ever, cities need to change and as an artist, I want to be part of this change and inspire others to embrace it. I am now working on two different collective garden projects in Lyon, where we just started growing dyeing plants for artistic and educational purposes.

I prefer using plants that I pick during walks in the city, in the nearby countryside or from my mother’s garden. In Lyon, I explore the city in search of dyeing plants. I can find and use Sophora Japonica flowers, buckthorn berries, pomegranate flowers, celandine, tree leaves from branches that fell down, blackberries, elderberries… I also love using edible plants and I admit I have a passion for red cabbage even though its colors are known to be very fragile to light.

I love the idea of working with plants that I already know and that I shared memories with. Behind each color there is a very special story to tell and this is also what I want to share with people. Having to follow the seasons is also very meaningful: it contributes to make the picking and ink-making or dyeing kind of unique. It teaches patience, gratefulness for what nature gives us, and allow us to grow roots where we live.

"Rêve de jardin" (Garden Dream) - Fresh Madder ink on torn piece of paper, black wallnut ink with nib pen - 2020

PlantKeepers, vegetal inks on paper (Sophora, Indigo and Wallnut), drawing with nib pen

Since last Fall, I have been working on two different series of works on paper called “Taking Over” and “Birth”. I just moved into a new workplace which allow me to work on bigger formats and I am actively looking for artistic residencies. I am also working on several songs I wrote about each plant I use. Lastly, I am working with Sustainable Art Market and developing new projects with the artists who are part of this platform.

People can follow my work on my website, gregoirefournier.com, where they can discover the current series I am working on and watch full-length videos.

You can find me on Instagram: @gregoirefournier. I am also posting on @chou.rouge, a page dedicated to the blue made out of red-cabbage (“Le Bleu du Chou Rouge”).

Caroline Ross

My creative practice changes with the seasons and the years, responding to gluts and shortages in foraged goods, gift ochres arriving from friends, feathers moulted by the swans, a finding-trip to a new environment. It has not always been so. For many years I told myself what to do, what I was allowed to do, to draw, to make. How I came to be mainly free of the vice-like grip of the machine is a meandering story, but here’s the gist.

Featured Artist Series

This is part of a series of blogs featuring inspiring artists and craft people who work with local natural materials.

Caroline living in the woods for a week just off to get water, nettles and chalk

My creative practice changes with the seasons and the years, responding to gluts and shortages in foraged goods, gift ochres arriving from friends, feathers moulted by the swans, a finding-trip to a new environment. It has not always been so. For many years I told myself what to do, what I was allowed to do, to draw, to make. How I came to be mainly free of the vice-like grip of the machine is a meandering story, but here’s the gist.

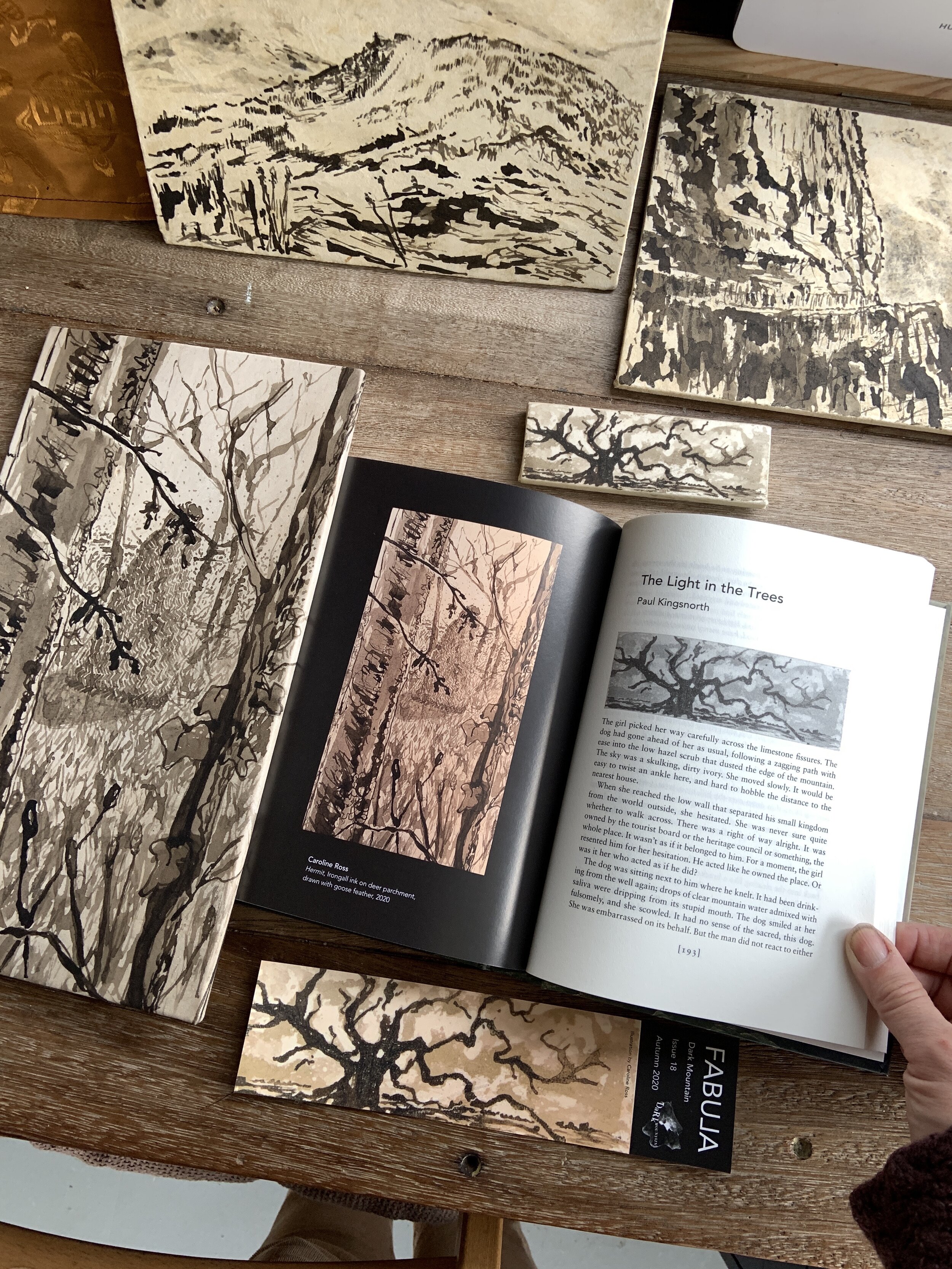

Artwork in current Dark Mountain Fabula

After 6 years at art college, and an MA in Painting from Chelsea School of Art, in 1996 I still had no clue where I could belong in the London art world. I have drawn since I could hold a pencil, and that’s why I wanted to be an artist, drawing gives permission to pay attention to the world in detail. That inquisitiveness was why my other love at school was science, particularly chemistry and physics. I had a fantastic 2-year Foundation course at Shelley Park, Bournemouth, a dedicated foundation art college taking up the whole of the historic home of Mary Shelley and her son, where she came to live after the death of her husband the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Here I had been shown real gold: colour theory, drawing skills, printmaking, photography, ceramics, textiles, and so much more, by people passionate about their work and about teaching. Stepping out into the world 6 years later, I knew that my enthusiasm and multiple artistic inclinations would see me labelled as eccentric, or worse, the dreaded insult: earnest. So, like so many artists before, I formed a band, and for 10 years played music, sung, toured the world and recorded records, formed a record label, co-ran our recording studio, all in a team; because to make art this way with others using sounds and words felt right.

Ink drawing from autumn 2020, oak gall ink on rag paper.

When I was living up in Aberdeenshire, visual art slowly came back into my life, and I have Deveron Arts (now Deveron Projects) to thank for that. Being part of a wider art scene in a much more sparsely populated rural area meant that when we put on an event or had something musical or creative to teach or show, that there was an audience who were not jaded or overwhelmed with a panoply of events. The world of individual artists as megastars seemed very far away, (despite our old ‘gang’ in London having included Turner Prize winner, due to my then husband co-founding the studios and gallery, Cubitt Artists). Now, surrounded by trees and deer, hawks and rivers, I found the seeds of a new way to make art, that would flourish when I returned to London in 2006, mainly to study more deeply with my T’ai Chi master, after 6 years away.

Basket of materials which lives next to my drawing desk

Finding The Dark Mountain Project in late 2014 changed the course of my art life again. I had returned to drawing with a passion and was studying Renaissance and traditional art materials at The Royal Drawing School with Daniel Chatto. When I read Paul Kingsnorth’s ‘The Wake’ after it gained a glowing review in the Guardian and did something I rarely do: looked up the author. This led me to Dark Mountain, and to going to their events, submitting art and writing, and now, years later, finding DM near the core of my artistic practice, how I show work, and who I collaborate with. Here at last, and also now with The Wilderness Art Collective, I found a broad group of artists and writers, makers and thinkers who also create work in the context of our living planet under great threat. It seems to me slightly ridiculous to make art of any kind that wilfully ignores this existential planetary predicament. Business as usual is the way of commerce and politics, and almost to be expected. But seeing this common in cultural worlds was depressing. In 2017, when asked by Paul to introduce myself to participants on a workshop I was teaching at Way Of Nature’s ‘Fire and Shadow’, a voice from inside me blurted out, to my own great surprise, ‘I am a devotional artist.’

Small works in handmade natural watercolour paint on deer parchment for Dark Mountain Sanctum

The last 4 years have been a journey into finding out what that spontaneously uncivil savant meant. ‘Devotion’ is an unpopular term, old-fashioned perhaps. But it sums up how I feel about earth.

Grave goods

So far, this journey means no longer dictating form. It means using almost entirely natural materials, foraging and finding, reusing and researching. The inconsistencies and quirks of materials which are not machine-made keeps me attentive and absorbed. Time and practice have synthesised 25 years of T’ai Chi and Tao, my love of bushcraft and wilderness skills, and my drawing and crafts into one thing. Often this takes the form of drawings with a quill pen in iron gall ink on deer skin parchment and paper books, all of which I make myself from waste materials. Sometimes I work for a period exclusively on Grave Goods, an ongoing collection of items and garments which I intend to be buried with me. I’ll be showing some of these at ‘Borrowed Time’ in November, and they’ll be in the next Dark Mountain book this spring. I teach life drawing, practice various fibre and textile arts, make leather and buckskin, and find time for other natural material handcrafts using bark, wood, stones, bone and so on. I find sanity in grinding ochres for paint, making ink from botanicals and plying cordage from plant fibres. My work is found in magazines, books, periodicals, sometimes in shows in galleries or online, but most often within the pages of Dark Mountain. Much of my work is bought privately and now has a life on the walls and in the homes of people all over the world, who may have seen it on my website or on Instagram. It is good for my art to have its own life, beyond my little boat, and to be in relationship with other eyes and minds.

Ink and paint materials

I forage rather than grow most of the plants I use, particularly oak galls, lime tree inner bark, prunus gum and leaves and nettles. In 2020 I was about to start an allotment of plants for inks, but arthritis has meant this isn’t possible just now. However, I was always a gatherer, and though I would love to again be a gardener, the riverbanks and seashores where I spend most of my time offer such a wealth of materials to the ethical forager, I would barely have time to tend the woad, madder or marigolds I had planned for the year ahead. Swaps with other colour people are common and a huge joy. I provide a yearly pigment for the Wild Pigment Project, which is a source of real community and learning for me. Right now two parcels of ochres are on their way to Tilke Elkins, and post gods willing, should be winging their way round the world in the late spring.

Badger dug chalk

A constant in my life since childhood has been a procession of inspiring and talented teachers. Some teachers who have been really instructive for me since returning to England have been Joe O’Leary (@joescraft), Theresa Emmerich Kamper (@traditional_leather), Daniel Chatto, David Cranswick (@alchemyofpaint). Mostly I prefer to learn skills in person, and then practice on my own. Books come a close second. Videos come last, which is ironic, as that’s what I get asked most to create for my own students. So I am rather latterly teaching myself to make and edit instructional films, as Paul Kingsnorth and I will be teaching Wild Twins Course for the third time this year, but online rather than in the wilds of Cork, Ireland. We bring words and the image together, using myth and story, hand making all our materials, sending ourselves out into the wild to really listen to nature. It’s a distillation of all the work we both care about, and I am so looking forward to teaching it this April. All 18 places filled up and I feel really lucky to soon share what I love.

Back deck view

After being suddenly evicted from my purpose-built boat studio and mooring last September, I now work in the saloon of my new little boat upriver and store all my materials here and in my new shed. It may not be ideal, but it was warm and convenient over the winter, and I got on with lots of projects. 2021 sees teaching Wild Twins, an ink residency at @knockvologan.studies on Mull, creating site-specific art materials at The Sidney Nolan Trust with Wilderness Art Collective in the summer, and exhibiting Grave Goods and talking at Borrowed Time symposium at Dartington in November. In 2022 I will hopefully be working on a Dark Mountain book collaboration, which I can’t talk about yet!

Teaching paint making on the Wild Twins Course

My feeling is, after almost 50 years on this incomparable planet, among beloved human and non-human neighbours, that my art is a natural response to how things are for this particular organism, moment to moment. This means I will never be someone who bangs out a cohesive-looking body of similarly made work for 20 years and has a gallery to represent them. Instead I shall remain a tributarian, a meanderthal, a craftcrastinator, found in nooks and cracks like a dandelion or an ink cap, and be happier for it. For many years, my art came out in lyrics, melodies, harmonies and basslines. Now I take a line for a walk with a quill dipped in blackest ink. But looking back from where I am now, I can see the winding path through it all, and am still really interested to see where it will lead. So I will stay out here to make art where earth matters, sending tendrils out into the wider world with the brambles and rocks, as part of nature, and not in the airless hall of polished mirrors that is the mainstream (so-called) culture.

Links to all my recent work, exhibitions, publications, essays and projects can be found at www.carolineross.co.uk . There are also regular posts from my process at Instagram @foundandground

You can search for my name at www.wildernessart.org to see work from the recent show ‘Wilderness of the Mind’.

www.dark-mountain.net has two essays, including one about my ochre on rock artwork for the cover of issue 13. My art and writing are in 7 issues of the book from issue 9 onwards.

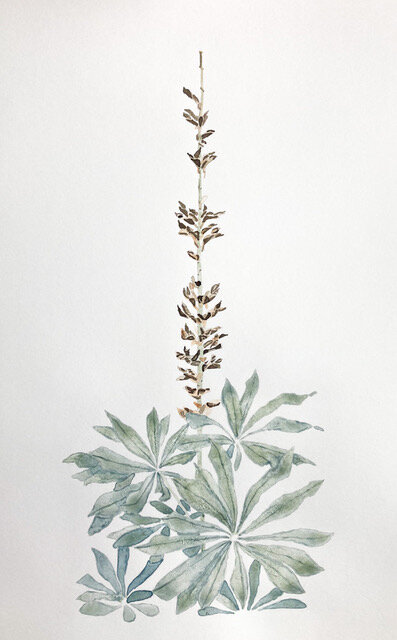

Sophie Twiss - Botanical Dreams

I enjoy the stories that reveal themselves when learning about plants. Morning glory is an introduced garden ornamental and invasive plant that has taken strangulating hold here; the beautiful glowing iridescent purple blue flowers smother the local plants. I have used it to make inks and dyes and have used the vines to weave. I use what is abundant and until now didn’t grow any dye plants, I would have to investigate the appropriateness of introducing any plants and have been happy so far to explore what already exists here.

Featured Artist Series

This is part of a series of blogs featuring inspiring artists and craft people who work with local natural materials.

I grew up in Durham, in the North of England and I live in a Santa Lucia, a small village in the South of Spain. This informs the way I work since working with the plants around me was a process of learning, familiarising and integrating myself with my surrounding environment. Getting to know the species that I share space with, observing patterns of growth and paying attention to what happens around me. In my arts practice I use materials that I encounter, exploring narratives of place through material and processes.

I enjoy the stories that reveal themselves when learning about plants. Morning glory is an introduced garden ornamental and invasive plant that has taken strangulating hold here; the beautiful glowing iridescent purple blue flowers smother the local plants. I have used it to make inks and dyes and have used the vines to weave. I use what is abundant and until now didn’t grow any dye plants, I would have to investigate the appropriateness of introducing any plants and have been happy so far to explore what already exists here.

One of my favourite colour sources is from acebuche, small wild olives which make purple, blue, pink and red. I probably started investigating dye plants because of this, seeing the deep colour stains under the acebuche trees, and in the bird droppings – I thought that if it still retains the purple colour after being processed through the body of a bird then it is an interesting colour! And it is a very sort of authentic expression of this place, the wild olive trees are ancient rooted. Oxalis flowers paint the countryside yellow in spring and make a deep sunshine yellow that I love. I am lucky to have an abundance of walnut, avocado and pomegranate trees too.

I have a special affinity with certain plants like Alexanders, they don’t make the strongest dye colour but I like it very much and I love to see them appear each year. I had no interest in working with insect dyes but prickly pear cactuses and cochineal are quite common in this area – both are considered invasive species and beginning to learn about them was like opening a book about history, colour trade and ecology which I found fascinating. When a neighbour gave me cochineal covered leaves from a dead cactus curiosity got the better of me and I was astounded by the deep colours that I extracted.

The dome was an idea I had when I first began to experiment with plant colours. I would create libraries of colour swatches. I liked to play, experiment, process and mostly just enjoyed to see the expanding colour palette. I would cover my walls in colour swatches and samples. I saw them as a sort of abstract map of the local environment, since I was only using what grew around me.

In seeing the collections of colours I wanted to create a space where they could be contemplated together as a whole, a landscape colour map. I had previously worked a lot with geometric shapes, I was interested in patterns of growth and the dome was a good resolution in bringing these ideas together. There was a long process of gathering and dyeing. I learned how to dye better mid way through and if I would start again now I would probably have much stronger colours but I like how it is also exists as testament to my learning process and experiments.

To make the dome was great experience, to start with an idea and see it fully realised (with a global pandemic in the middle) yet not quite knowing until it is completed how it will look and feel. It was first mounted by my home where it was created and felt harmonious. The colours distilled from the plants dialoguing with the same plants in the environment. To view it from outside and then to experience it inside, to see the sun and reflections of plants through the material was quite special. It is currently exhibited by the Barbate river that flows through this area. From there I would like to take it to different landscapes in this area, to inhabit the environment from which it was created.

I made a quilt with the scraps of material leftover from the dome which was a really positive personal experience. I had very little sewing skill or knowledge before I started but was able to make what would become a very precious object to me. It was a process of accepting imperfection; lots of the triangles don’t meet as they should, there are ruffles, pleats, wonky stitches but the overall whole is beautiful. That was a huge lesson or me. I want to sleep in the dome with the quilt when spring comes and it is dry and warmer. I call the work Botanical Dreams, this was what I had named it from the beginning, before I’d even thought to make a quilt so it is fitting that the quilt became part of the dream.

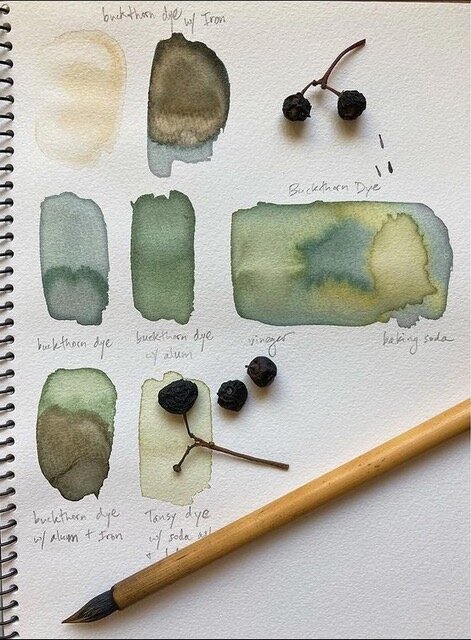

Handmade inks

I continue to experiment with different ways of working with plants. I have been experimenting with watercolours from plant pigments and made charcoal from willow which was really inspiring. I love the seasonal nature of working with plants and the constancy, if I miss something it will come around again. I am currently working on a couple of projects, about moth biodiversity and another about urban insectivorous birds. They are quite different but are actually both connected to plants – when looking at moths it is relevant to look at available plant food sources and the insectivorous birds migrate following the abundance of insects which come with Spring and the blossoming of plants – everything is connected and the network of relationships with plant life is fascinating and complex.

My work can be seen on my website: https://sophietwiss.com/

I keep a (not so constant) Instagram account at: _stwiss_

Carolyn Sweeney / Strata Ink

I have an abiding passion for plants, particularly the plants native to my home in the Pacific Northwest. When I discovered I could make ink from many of the plants I was already familiar with it kindled a childlike enthusiasm. My work typically depicts plants I have sketched in the field and then reworked in the studio with my own homemade natural inks. This is a true investigation of place from rocks to soils to leaves.

This year I am focusing on creating a line of artist quality, lightfast, all natural inks in a full range of colors. Most of the pigments are made from rocks, soils, and plants I have foraged myself. I have been making my own inks and watercolor paints from foraged natural materials for many years now, but making a full range of colors is a new and inspiring challenge.

Featured Artist Series

This is part of a series of blogs featuring inspiring artists and craft people who work with local natural materials.

My artistic practice is driven by curiosity and exploration. I have an abiding passion for plants, particularly the plants native to my home in the Pacific Northwest. When I discovered I could make ink from many of the plants I was already familiar with it kindled a childlike enthusiasm. My work typically depicts plants I have sketched in the field and then reworked in the studio with my own homemade natural inks. This is a true investigation of place from rocks to soils to leaves. These paintings are a testament to the abundance of beauty all around us. I believe the simplest elements in life can sometimes be the most rewarding- a bright red ochre, the deep brown juice of a discarded walnut husk, sunlight falling on a leaf.

Harvesting Chamisa for Lake Pigments

Gathering Red Ochre from an Orgeon Road Cut

I live in Portland, Oregon and I prefer to forage for my materials. Living in the city I have limited access to land. The yard that I do have is too shaded to grow most dye plants. In wild areas of the city I find an abundance of plants suitable for ink making. I keep a mental map of the useful plants in my neighborhood. As the seasons change I alter my daily walking routes to visit the plants I want to harvest in any given season. I also look out for neighbors who are growing dye plants, like coreopsis, as ornamentals. One neighbor with a particularly robust coreopsis patch in her front yard has given me permission to deadhead her plants. I take the dried up flowers and she is happy to have someone clean up her plants throughout the summer. This summer I gathered tansy flowers and goldenrod from an urban natural area and used them to make lake pigments. There are lots of black walnut and chestnut trees in my neighborhood so I gather the husks of those in the fall. Prunings from neighborhood fruit trees make for good winter inks. Right now I have an abundance of pruned bay laurel branches. When I keep my eyes open I find more plant matter for ink making than I could ever use. One neighbor’s waste is another neighbor’s treasure!

This year I am focusing on creating a line of artist quality, lightfast, all natural inks in a full range of colors. Most of the pigments are made from rocks, soils, and plants I have foraged myself. I have been making my own inks and watercolor paints from foraged natural materials for many years now, but making a full range of colors is a new and inspiring challenge. Each ink is made from pigment and homemade watercolor binder which I mull on a glass slab. When I paint with the inks it is a completely different experience from using commercial paints. These natural colors make sense to me. They have become an integral part of my work. Gathering and processing my own pigments is very time consuming, but I enjoy making the inks as much as I enjoy painting with them. When I sit down to paint with the inks I feel I am having a conversation with friends. The inks have come from places that are intimate to me and I carry that intimacy and fellowship into my painting practice.

In the past I struggled to depict the natural world with the bright watercolors I bought off the shelf. Once I began using natural pigments the subtlety and nuance I was looking for was right in front of me- layers of color in one ink, color that that changes as it dries, color that breaks and bleeds. I want to share this experience with others. Painting with natural inks is a form of color therapy for me. I feel intense joy simply painting a row of swatches and watching the colors unfold. All of the colors blend beautifully. There are no wrong notes, just new cords to play. Using these inks has built my confidence in my own work and given me abundant fuel for experimentation. I believe that I am just at the beginning of my explorations. The more time I spend with the inks and colors the more fluent I feel in using them.

I have been quite isolated from people this winter due to Covid restrictions and a partner who is out of the country caring for an elderly parent. Working with plants and ochres has been a deep comfort to me. Foraging for them and processing them into ink has woven me more firmly into a network of connections outside of human relationships. That grounding in place and season is an antidote to loneliness. There is so much wonder and connection just outside my doorstep that even in the city I feel embraced by my place within the natural world.

My website is strataink.com where you can find my collection of natural inks. The best place to follow my ink making process and artistic practice is on instagram @strataink. I am also on Pinterest @Strata_Ink. I look forward to connecting with you there.

Alice Fox

Featured Artist Series

This part of a series of blogs featuring inspiring artists who make their own natural materials.

Please tell us about your creative practice? My practice is based around using materials gathered and grown, mainly at my allotment plot. I trained in textiles after a short career in nature conservation. My work is underpinned by a strong passion for the natural world and a desire to work sustainably. I completed an MA in Creative Practice a couple of years ago and this helped me to really focus on the materials available to me on the allotment. I use plant fibres for making cordage (I’m exploring various soft basketry techniques at the moment) as well as processing and spinning flax and nettle for yarn. This is highly labour intensive for small amounts of usable thread, but the process is as important to me as any ‘finshed’ outcome.

This is part of a series of blogs featuring inspiring artists and craft people who work with local natural materials.

©Carolynmendelsohn

Please tell us about your creative practice? My practice is based around using materials gathered and grown, mainly at my allotment plot. I trained in textiles after a short career in nature conservation. My work is underpinned by a strong passion for the natural world and a desire to work sustainably. I completed an MA in Creative Practice a couple of years ago and this helped me to really focus on the materials available to me on the allotment. I use plant fibres for making cordage (I’m exploring various soft basketry techniques at the moment) as well as processing and spinning flax and nettle for yarn. This is highly labour intensive for small amounts of usable thread, but the process is as important to me as any ‘finshed’ outcome. That engagement with the plot and everything that goes into nurturing, harvesting and then handling and coaxing fibres from the plants is completely immersive and imbues the resulting threads (and what I make with them) with so much more meaning than a commercially produced yarn. I use the plants that I grow for colour, for dyeing and for ink making, as well as botanical contact printing. I like to draw things from the plot using the inks made from allotment plants. Exploring the potential of everything on the plot constantly leads me in new directions.

How do you integrate natural materials in your practice? Natural materials are the basis of my work, but I also incorporate found objects in my work and will often experiment in bringing different materials together. There are a lot of plastics, paper, metal, ceramics and wood on the plot. I will make use of these when I can, even if it is just drawing them with the botanical inks.

Allotment shed & makeshift studio

Why do you choose to work with natural materials? I aim for my work to have as little impact on the environment as possible. Embracing natural cycles, working seasonally and using materials in a sustainable way are the key to my engagement with the plot and to my creative practice. I find natural materials beautiful and tactile – there is a kind of magic in taking something from the ground at the right time, processing it with care and coaxing it into a beautiful surface or structure. In some ways this is even more transformative if the fibre is classed as a weed or something unconventional as an art material.

Alice’s allotment

Where do you live and how does this influence your process of working with plants? I live in West Yorkshire, on the edge of Saltaire, which is part of Bradford. By using plants from my allotment (grown and self-seeded) I am using plants that are happy in the climate and conditions in my locality.

I understand much of your work is inspired by your allotment. Please tell me about your allotment? I grow a small amount of flax each year, to process into linen thread. I gather nettles on the plot, which are also processed for spinning. These are not sown but I encourage them to grow in certain parts of the plot. I gather brambles for fibre, bindweed stems and dandelion stalks from the margins of the plot and the wild bits in between allotments on the site. I use parts of plants that are grown primarily for food but that have fibrous leaves or stems, such as sweetcorn (husks), garlic (leaf) and other stems and strappy leaves as and when they are available. I grow various flowers as companion plants, but that can also be used as sources of colour – calendula, tagetes, coreopsis, sunflowers. I grew woad and weld for the first time last year, but I’ve generally resisted planting things specifically as dye plants, preferring to explore the potential of a normal working veg plot. I use wood from the various trees on the plot for ink making – apple, pear, beech and peach.

Dandelion braid with stone - Alice Fox

What processes are you drawn to and why? I am most comfortable with thread-based processes, resulting in constructed surfaces and structures. This might involve weaving, stitching, looping, twining, braiding… There are lots of steps involved before some of the fibres I work with become useable threads and each fibre requires slightly different handling or processing.

Freshly gathered bramble fibre - Alice Fox

What are the challenges to working with natural materials? Materials are only available at certain times of the year and the cycles of harvesting, drying, processing etc. take time. If you miss a window of opportunity you have to wait another year. Crops of each fibre are not necessarily abundant, but this makes them more ‘valuable’ as a result. It is easy to lose a year’s crop of something if stored badly – things can very quickly go mouldy if damp. Usable fibre has a long lead-in time but some of the colour-based activity can be much more immediate, enabling different ways of recording and mapping through drawing and printing.

What are you working on in 2021? I am developing a body of work that brings a series of found objects from the plot together with plant fibres. I am also working on a new book this year, which explores lots of the themes of my work.

How can people access your work?

My website features various exhibition projects I’ve undertaken, as well as listing workshops and exhibitions. I have published a number of books, which are available to order via my website. Plot 105, which I published last year, is all about the ways I use my allotment plot in my practice.

Website: www.alicefox.co.uk

Instagram and Twitter: @alicefoxartist

Facebook: www.facebook.com/alicefoxartist